Do you have trouble losing body fat, yet seem to gain it after even the smallest slip up with your diet? Or does it feel like you can eat for days without gaining an ounce? It could have something to do with your current body type. But is it really that simple?

Let’s explore the three body types more in depth – endomorph, mesomorph, and ectomorph – and analyze how they relate to overall body composition.

WHAT IS BODY TYPE?

Body type, or somatotype, refers to the idea that there are three generalized body compositions that people are predetermined to have. The concept was theorized by Dr. W.H. Sheldon back in the early 1940s, naming the three somatotypes endomorph, mesomorph, and ectomorph.

It was originally believed that a person’s somatotype was unchangeable, and that certain physiological and psychological characteristics were even determined by whichever one a person aligns to.

According to Sheldon, endomorphs have bodies that are always rounded and soft, mesomorphs are always square and muscular, and ectomorphs are always thin and fine-boned.

He theorized that these body types directly influenced a person’s personality, and the names were chosen because he believed the predominate traits of each somatotype were set in stone, derived from pre-birth preferential development of either the endodermal, mesodermal, or ectodermal embryonic layers.

THE BODY TYPE SPECTRUM

So then why are we even discussing this topic? Because while the notion of a predetermined body composition looks far-fetched through a 21st century lens, many of the physiological markers and observations associated with each somatotype do actually exist in the greater population.

However, the modern understanding is flipped from Sheldon’s original concept; it’s our physiological characteristics that determine the current somatotype, not the somatotype that determines our collective physiologies.

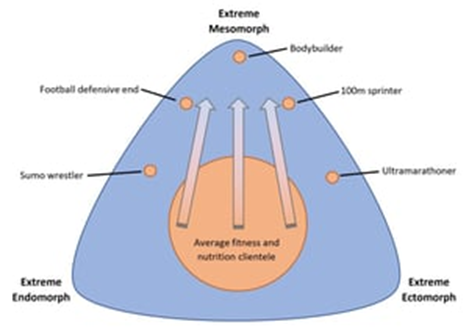

No one exists within purely one somatotype; instead, we are all constantly in flux and fall uniquely on a spectrum somewhere between all three.

HOW TO IDENTIFY BODY TYPE

In light of all this, understanding a client’s current-state body type is quite beneficial for fitness professionals. A simple observation of body composition can help quickly identify various physiological situations a client might be dealing with and allow you to tailor solutions that will preferentially address each one. Use the following somatotype traits to determine which one a person primarily aligns to:

ENDOMORPH

- Stockier bone structures with larger midsection and hips.

- Carries more fat throughout the body.

- Gains fat fast and loses it slow.

- Naturally slow metabolism; potentially due to chronic conditions (e.g., thyroid deficiency, diabetes) but too frequently the result of a sedentary lifestyle and chronically-positive daily energy balance.

MESOMORPH

- Medium bone structure with shoulders wider than the hips.

- Developed athletic musculature.

- Efficient metabolism; mass gain and loss both happen with relative ease.

ECTOMORPH

- More narrow shoulders and hips in respect to height.

- Relatively smaller muscles in respect to bone length.

- Naturally fast metabolism makes it difficult for many to gain mass.

- Potentially indicative of disordered eating (e.g., anorexia, bulimia) when BMI is ≤17.

Once you identify which somatotype a client most aligns to, consider the structural and metabolic challenges that are associated with it. Then, tailor the exercise programming and dietary coaching to overcome those hurdles. This will preferentially develop the necessary foundation that each client individually requires.

For the typical new client, the initial, overarching goal to “get in shape” will essentially boil down to a desire to shift their current-state body type toward a more mesomorphic physiology.

Obviously, there will be exceptions to this rule – there will always be endomorphs who want to get even bigger to compete in strongman events and ectomorphs who want to keep thin and trim for running ultramarathons – but it rings true for the majority of clients seeking the help of a Certified Personal Trainer or Nutrition Coach.

In light of that average goal, for example, a client who presents predominately as an ectomorph will most likely need dietary and training solutions that focus on muscle protein synthesis and overall mass gain, while typical endomorphic clients will benefit far more from frequent metabolic training and reduced calorie intakes. So, take a look at each individual, critically evaluate whether you are using the right methods for the body type they currently display, and use the following tips to better tailor your programs for maximal success.

HOW TO IMPROVE YOUR BODY COMPOSITION

Research continues to prove that physical training and consistent, habitual changes to the diet have a strong influence on improving body composition. Metabolic conditions such as hyper- or hypothyroidism are fully within the realm of modern medicine to manage and improve, and chronic conditions like type 2 diabetes are manageable and can even be remedied in many cases through improvements to diet and exercise routines. Simply type “[exercise/diet] impact on body composition” into your favorite search engine and quickly become overwhelmed with the breadth of research spanning the last century.

The human body is highly adaptable and always seeks homeostasis (i.e., equilibrium) within its environment. But it can take a while to break old patterns that the body has gotten used to. This fact, that change takes time and consistency, is more than likely what leads many people to resign to the notion that they are stuck in a somatotype; because change is hard, and it’s often far easier and convenient to chalk one’s body dissatisfaction up to forces beyond direct control. But this is also where Personal Trainers and Nutrition Coaches have the most opportunity to build long-lasting relationships with clients.

Muscle is healthily gained at around one pound per month, and fat healthily lost at around one pound per week. After a desirable body composition has been attained through lifestyle modification, physical training, and healthy changes to diet – and, more importantly, when those new habits are adopted and maintained permanently – the new body that is symptomatic of all those changes will eventually become the “new normal.”

Metabolisms and appetites adjust to new energy intakes, physical activity becomes a natural part of the day instead of a chore, and someone who was predominately ectomorphic or endomorphic will eventually see themselves displaying far more mesomorphic traits over time.

HOW TO TRAIN ENDOMORPHS

Training endomorphs should predominantly focus on fat loss techniques until a desirable body composition and functional cardiorespiratory efficiency have been achieved. Resistance training should be used to strengthen muscles and stabilize joints to support more-efficient movement elsewhere in life, but this population tends to need cardiorespiratory improvement and fat loss above all.

In the gym, work through a basic entry-level periodised training program, but keep the majority of training sessions focused on metabolic conditioning. Use short rest periods, circuits for resistance exercises, lots of plyometrics (within client tolerance), and use as much additional time as possible for steady-state cardio.

Consistent anaerobic and aerobic training will help endomorphic bodies increase their metabolic efficiency and boost the body’s daily energy requirement. Additionally, recommend that primarily-endomorphic clients increase their non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) factor as much as possible, moving more during times of the day when they’re not in the gym. Commitment to a less-sedentary lifestyle overall is the most important thing for this population to begin overcoming their metabolic challenges.

Due to those slower metabolisms (regardless of the underlying cause) and a surplus of stored energy (body fat), nutritional solutions for primarily-endomorphic individuals should focus on techniques to maximize fat loss while still supporting, and even building, the existing lean muscle mass. To accomplish this, a diet that is both low-calorie and high in protein is ideal. Diets containing daily protein of as much as 2.2 grams per kilogram body weight (and sometimes even higher) have been shown safe and effective for supporting existing muscle tissue during times of calorie restriction and weight loss.

After ensuring that daily protein requirements have been met, the remaining pool of calories can come from whatever blend of carbs and fats the individual best tolerates. Some may tolerate a very low-carb “ketogenic” diet that helps them preferentially burn even more fat throughout the day, while others will experience hypoglycemia and its associated nauseating symptoms without enough carbohydrates in their diet.

This rings especially true during workouts, where carbs are important to fuel the higher intensities needed for cardiorespiratory improvement. But regardless of whether carbs or fats are the preferred source of energy, the most important thing is to determine the client’s total daily calorie requirement and keep food intake a bit lower (with still-ample protein) so that the body remains in a negative energy balance with as little muscle catabolism as possible.

- Maximize calorie burn and the improvement of metabolic efficiency by primarily using high-intensity, metabolic training techniques.

- Consume a high-protein diet with balanced carbs and fats that maintains a slight negative energy balance.

HOW TO TRAIN ECTOMORPHS

Ectomorphs face the opposite set of challenges as primarily-endomorphic individuals. Due to the numerous factors previously mentioned, most ectomorphic clients have developed bodies with highly active metabolisms and “lanky” bone structures, making it hard for them to put on mass and keep it on. For this reason, exercise techniques for hypertrophy and maximal strength should be prioritized, with a greatly-reduced focus on cardiorespiratory training to reduce overall energy utilization.

After working through the initial phases of an entry-level training program, the later phases where a focus will be on hypertrophy will be of most benefit to average clients in this population. Hypertrophy and maximal strength resistance training are primarily anaerobic in nature and, when combined with longer rest periods, won’t stimulate elevated calorie burn in the moment like more-intense, fast-paced exercise programs will. When paired with a consistently-positive energy balance, this type of lifting will preferentially help ectomorphs build up their body mass.

To accompany the mass gain-focused resistance training, ectomorphic bodies should eat a mass gain-focused diet. These individuals tend to burn through energy sources faster than most, so ample calories will be needed. Low-carb, fat-loss focused diets are not recommended here, and in some cases, it may be prudent to recommend that ectomorphic clients even incorporate “mass gainer” nutritional shakes into their diets.

And just like with endomorphic bodies that are working to become more mesomorphic, ectomorphs need high levels of protein too. 1.2 to 1.6 grams per kilogram body weight of daily protein has been shown to be optimal for muscle growth, with some individuals requiring up to 2.2.

That protein should then be spaced out every three hours so that muscle protein synthesis (MPS) signals (from the amino acid leucine) are maximized all day long. An additional protein shake at night, right before bed to minimize the fasting window, can also be beneficial for maximizing MPS in individuals with difficulty gaining weight.

- Maximize muscle gain using lower-intensity hypertrophy and maximal strength resistance training with longer rest periods.

- Consume a high-protein diet with balanced carbs and fats that maintains a positive energy balance.

HOW TO TRAIN MESOMORPHS

There’s no avoiding the fact that mesomorphs have things a bit easier than others. Their metabolisms are relatively efficient, they carry functional, if not athletic, muscle mass and are essentially ready to take on whatever fitness goal they please with minimal foundational work.

But remember, while there are undoubtedly some people who look lean and fit with zero effort, they are the exception to the rule. Most individuals who present a more-mesomorphic body composition have developed it as a consequence of numerous factors over their entire lifetime. And for formally endo- or ectomorphic individuals who have improved their lifestyles, diets, and fitness, hard work and discipline are the biggest factors of all.

A mesomorphic body type indicates a client is ready to transition to more advanced forms of power (like SAQ training), athletic, and sport-specific training. Comparatively, diets for mesomorphic bodies should be tailored specifically to health and fitness goals. Protein should be consumed anywhere between 1.2 and 2.2 grams per kilogram body weight depending on the intensity of the exercise program, with remaining calories coming from a blend of healthy carbs and fats. Then, if changes in body composition are still desired, the daily calorie load can either be increased or decreased to gain or lose weight, respectively.

- Utilize OPT Phases directly aligned to client goals.

- Eat specifically for fitness goals and activity, increasing or decreasing daily calories to preferentially control body composition with positive, neutral, or negative energy balances.

- Increase protein intakes to as high as 2.2 grams per kilogram of body weight for muscle gain goals; or, keep closer to the 0.8 gram per kilogram of body weight FDA recommended dietary allowance (RDA) when healthy body composition maintenance is all that is desired.

YOUR BODY TYPE IS NOT A LIFE SENTENCE

As they are understood and accepted today, body types reflect a generalized picture of how a person’s physiology is functioning in their current state. The observable somatotype represents the current sum of their physical, dietary, and lifestyle choices up to that point in time, combined with a variety of uncontrollable factors influenced by both genetics and the surrounding environment.

For example, at one extreme end of the spectrum, a person who has easy access to high-quality food, makes habitually healthy diet choices, is free of chronic disease, and consistently trains at progressively higher intensities will always have a more functional, muscular, and leaner body composition. On the flip side, someone who always sits all day and eats a lots of excess calories from junk food will undoubtedly develop the “soft roundness” stated in Sheldon’s original classification of endomorphs.

But remember, a body type is not a life sentence. If it were, personal trainers and nutrition coaches would all be out of jobs. The fitness industry, at its core, is all about helping people learn to use tools they can control (i.e., improved lifestyle, diet, and exercise techniques) to overcome challenges presented by genetic and environmental factors that they otherwise have no agency over.

Body type will shift based on lifestyle, activity, and diet modifications . Someone on the DASH diet will have a different composition than someone who doesn’t have a diet preference.

This notion is made clear when looking at average physiques of elite athletes in different sports, where consistent training and diet standards lead to similar average body compositions grouped across the somatotype spectrum.

Just to reiterate, a body type is not a life sentence. Just like a body mass index range isn’t a clearcut indication that someone is obese or underweight. There are many metrics at work.

STUFF TO CHECK OUT

For a great tool that calculates the amount of calories needed to hit weight loss goals, check out the NASM calorie deficit calculator. Also be sure to read up on How to Manage a Skinny Fat Body Composition.

REFERENCES

Bernard, TJ. (2003). Biography of William Sheldon, American psychologist. Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed online at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Sheldon

Carter, J.E.L. & Heath, B.H. (1990). Somatotyping – development and applications. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-35117-0

Carter, J.E.L. (2002). The Heath-Carter Anthropometric Somatotype, Instruction Manual. Department of Exercise and Nutritional Sciences, San Diego State University. Accessed online at: https://www.somatotype.org/Heath-CarterManual.pdf

Clark, M.A., Lucett, S.C., McGill, E., Montel, I., & Sutton, B. (2018). NASM Essentials of Personal Fitness Training, 6th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-1-284-16008-6

National Academy of Sports Medicine. (2019). Certified Nutrition Coach. Online education program, accessed at www.nasm.org

Toth, T., Michalikova, M., Bednarcikova, L., Zivacak, J., & Kneppo, P. (2014). Somatotypes in Sport. Acta Mechanica et Automatica, 8(1). DOI 10.2478/ama-2014-0005